Gone With the Wind Black and White Dress

We know what you're thinking. "This one?" "Of all the iconic dresses in Gone with the Wind, you're spending time talking about the least important one in the film?" "Where's the red gown? The draperies gown? The green-and-white barbecue dress?" Reader, we agree. Sort of.

It's true; this look could be said to have the least impact in the film and the story. The draperies gown, the red gown, and the barbecue dress hinge on plot and character points, furthering the story and/or illuminating the character of Scarlett O'Hara. They also, not coincidentally, have a far greater visual impact on film. They are memorable by design because the film's legendary costume designer Walter Plunkett understood that they would need to be so. When a script comments on a character's clothing, it's a signal to the designer to make sure the costume is up to the task, both visually and symbolically. When a script bases entire plot points and character progression points around such costumes, it's like shining the brightest possible spotlight on the designer's work. And generally, when a scene is written to portray the character actually getting dressed or figuring out how to make the item, it's a huge signal to the audience that you need to pay attention to what this costume is all about. It's why every superhero adaptation tends to come with a "transformation" scene built into the script, as we saw with Michelle Pfeiffer's Catwoman costume for Batman Returns.

Gone with the Wind is such a long movie, with such an epic sweep to it, that each time you talk about one of Scarlett's costumes, you have to situate it within its immediate surroundings, plot-wise. In other words, so much happens during the course of the film – and to Scarlett specifically – that each of her costumes represent her place or mindset at that point in the story. You can't talk about the draperies dress without establishing her desperation. You can't talk about the red dress without understanding her scandalous actions in the context of the time. You can't talk about the barbecue dress without understanding her agenda. And because this is her introductory dress; the costume she's wearing when the audience first sets eyes on her, you should look at what the film presented to you leading up to (and later, after) this moment:

Golden-hued romantic portraits of slavery in which the enslaved are underlit and in some cases barely distinguishable from objects of labor. They're not people, they're ideas. Symbols of the "Old South" of the title card. A signal that this is a story ostensibly about slavery in which the enslaved will be sidelined or treated as props. That framing is deliberate – and it's one of the many ways in which GWTW tries to have its cake and it eat it too. The film plays as being aware of the wrongness of slavery while cynically layering romantic imagery over it in order to appeal to the white audiences that were going to pay back the enormous amount of money sunk into the production. Which brings us (literally) to Scarlett:

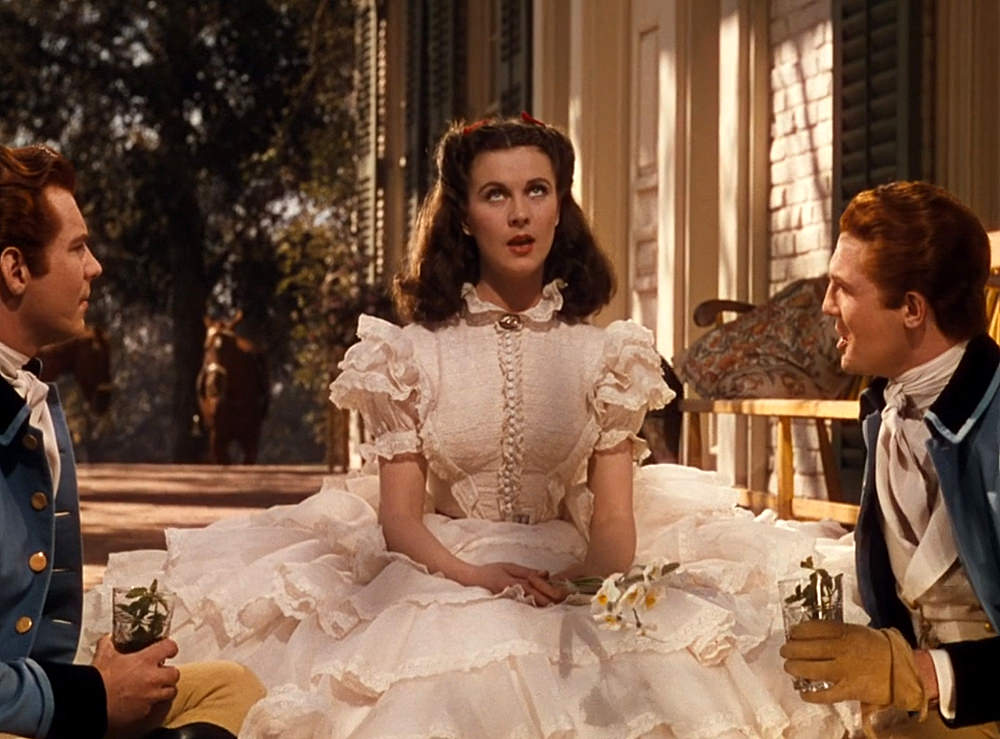

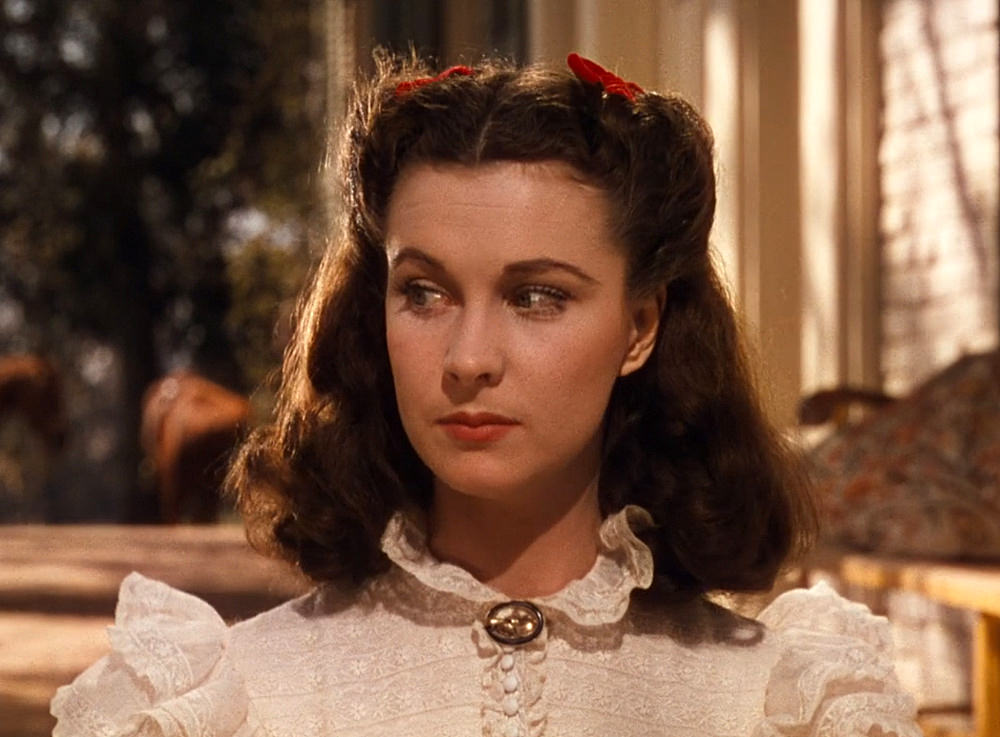

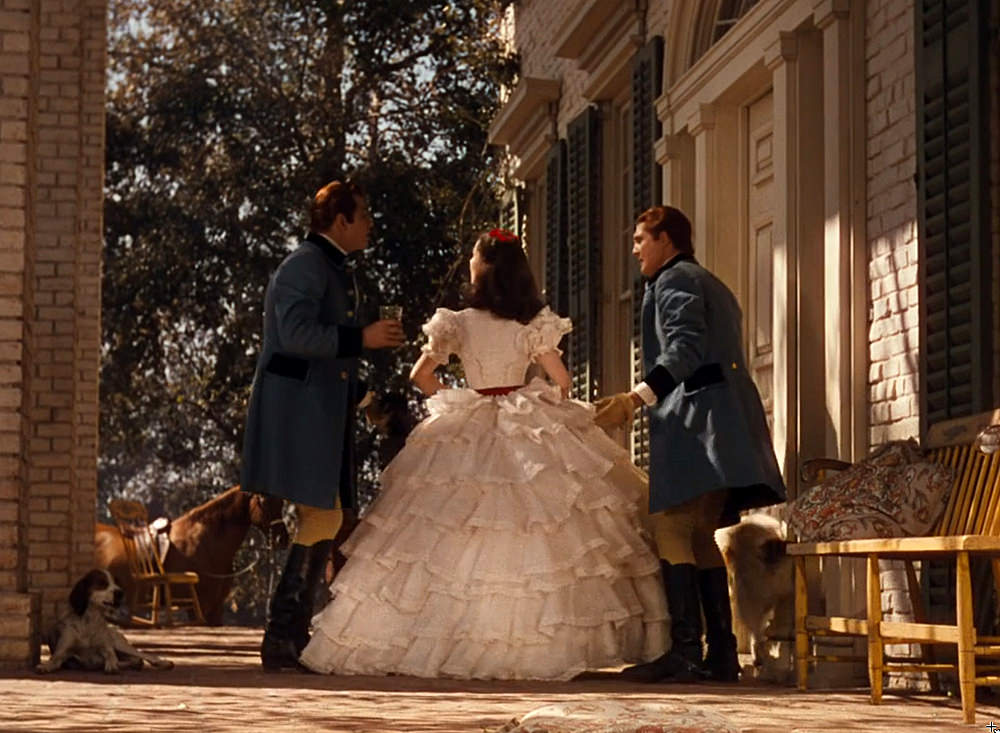

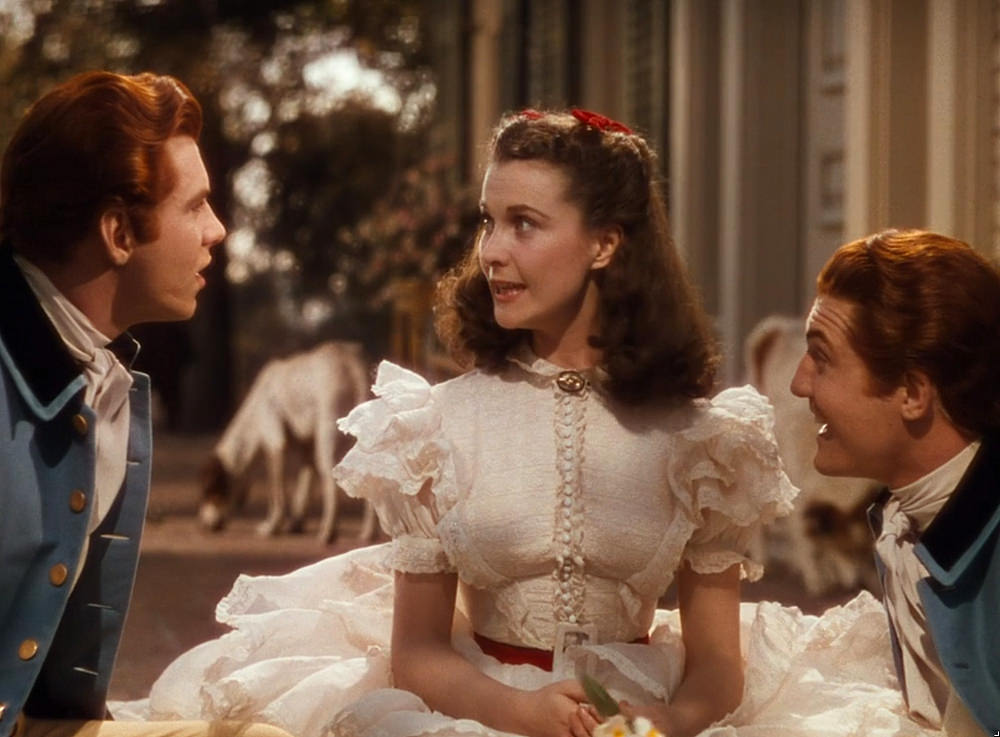

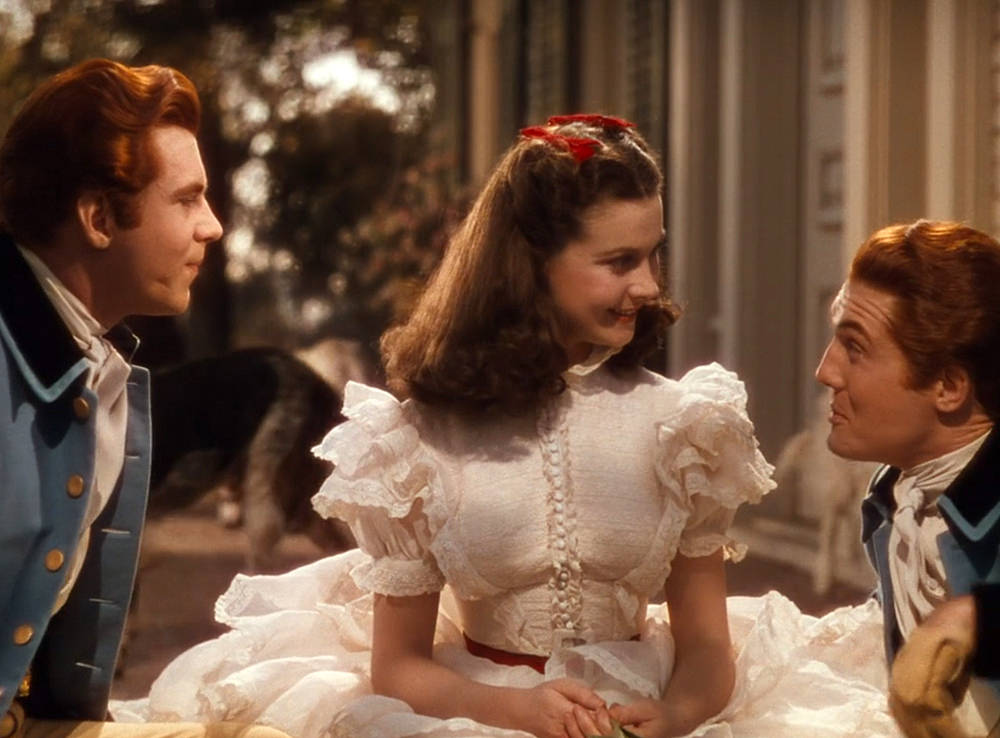

Notice how the framing obscures Scarlett until the last second; the way the camera dollys in on her reveal. The introductory aspect of the scene is underlined.

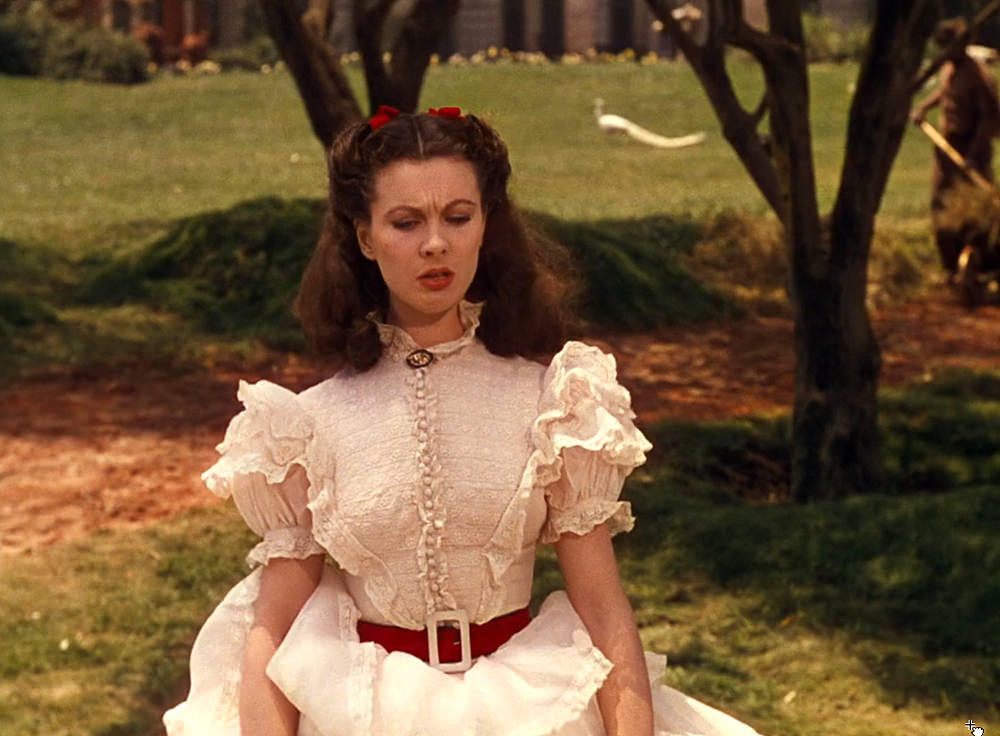

Here is your heroine; the person around whom the entire story revolves. The face of the Old South: white, pretty, and pampered. It should be noted that this was also something of a metatextual commentary on the epic casting search for Scarlett and the choice of Leigh herself, which was by no means an assured decision or one that would pay off for the filmmakers. As a British actress cast as what many saw as an iconically American heroine, Vivien Leigh was on the hook for making sure that the choice paid off. This shot and the subsequent scene are akin to a debutante's coming out ball, both in and outside the story. Here is your Scarlett O'Hara, America. Get a good look at her.

As such, the framing and general mise-en-scène are all in service to making sure all the light shines directly on her. Scarlett was already well-known to the huge numbers of people who made the book a rampant best-seller, but even now, eight decades later, to anyone who never read a word of Margaret Mitchell's novel, her character could not be made more clear to the audience.

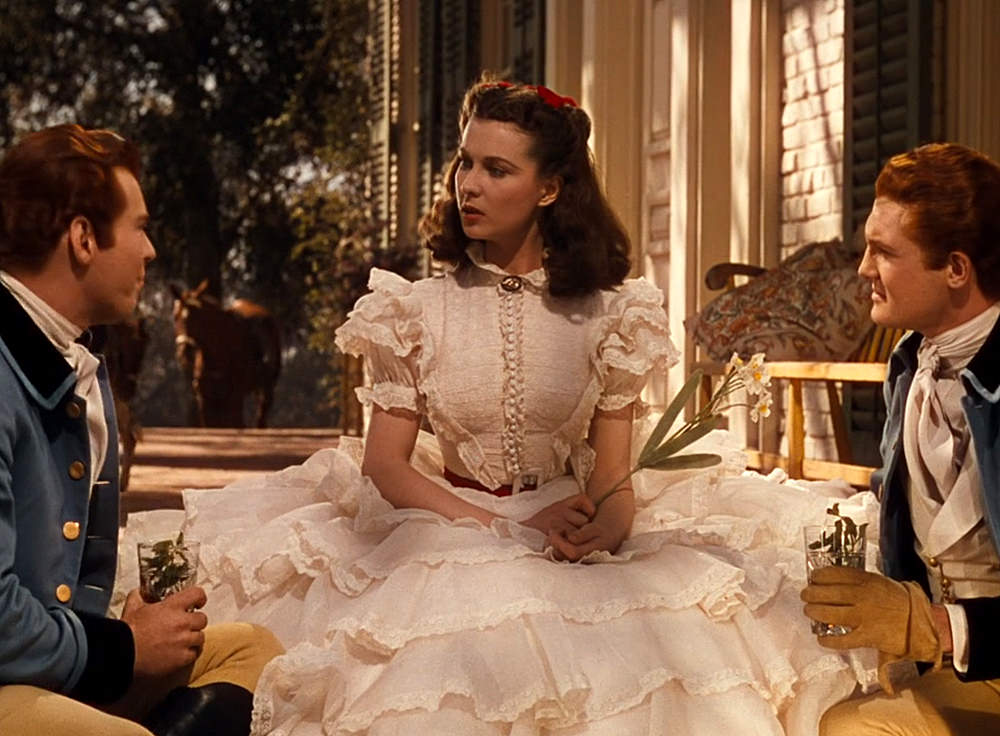

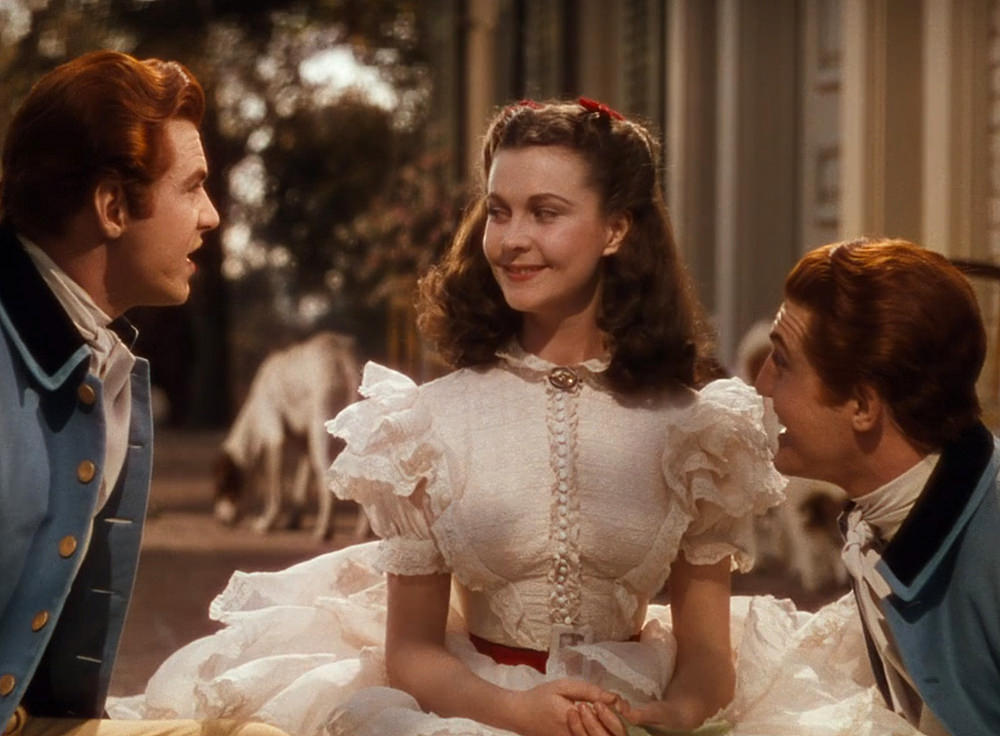

Sure, we can pay attention to the actual dialogue, which illustrates that Scarlett is frivolous and removed from the cares of the world (not to mention the ugly reality of her lifestyle), but we could just as easily get a sense of her from looking at these screencaps.

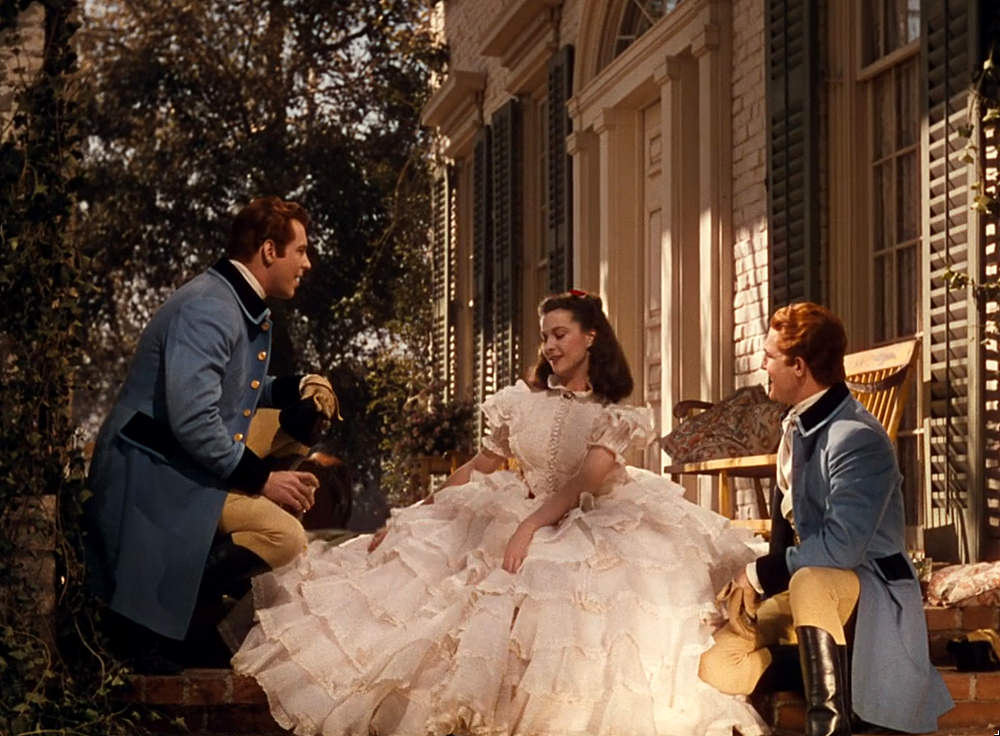

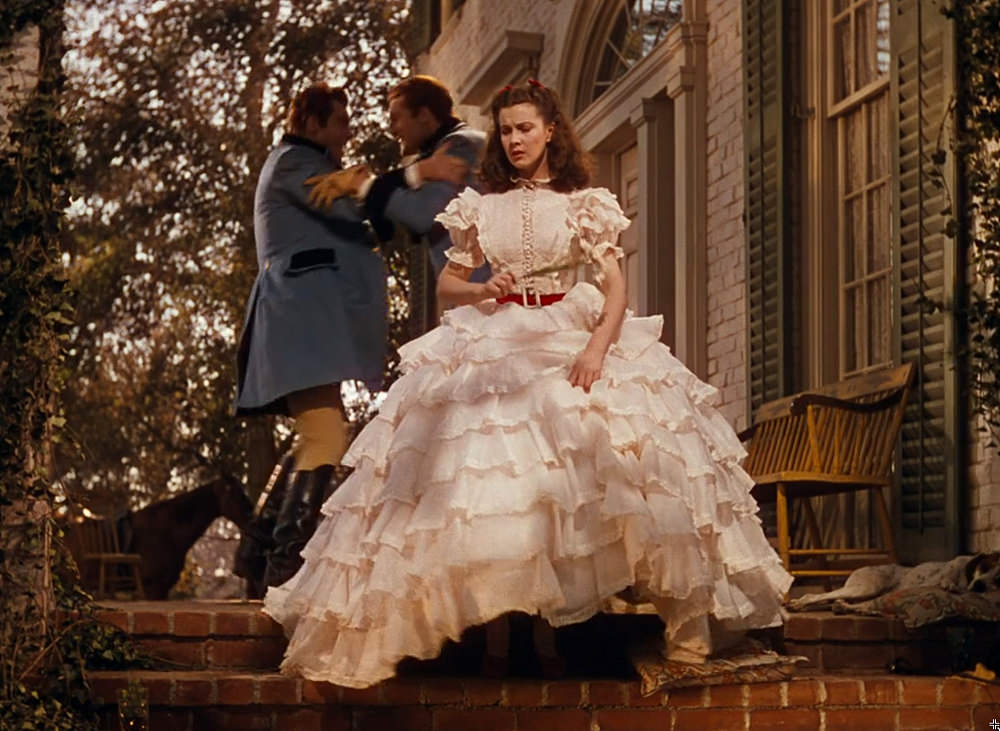

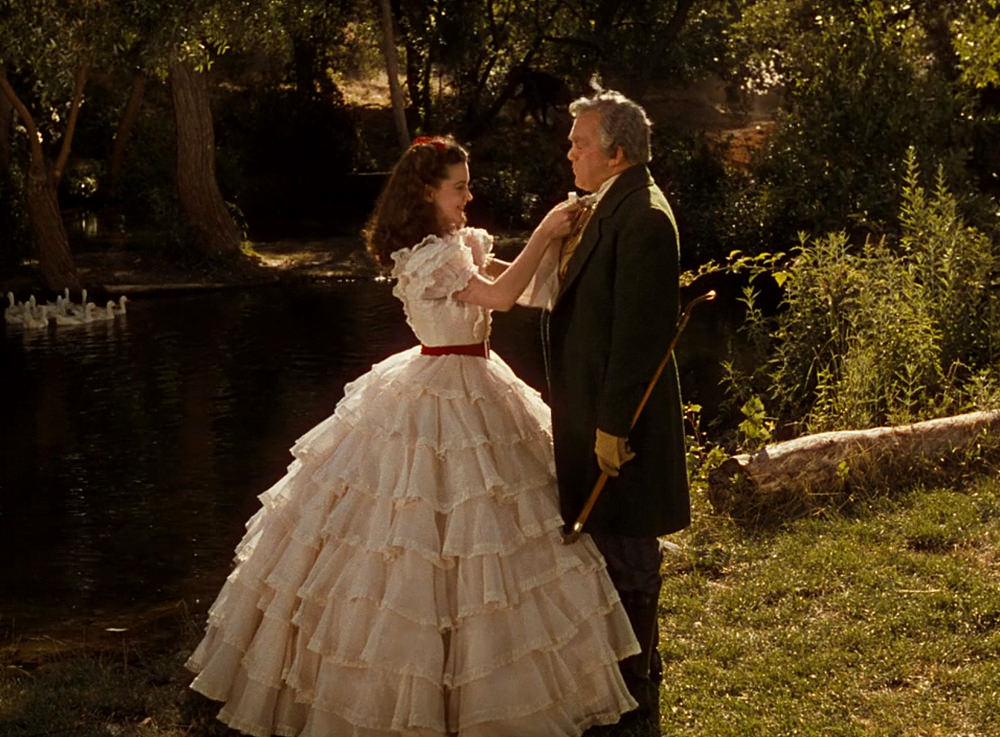

She is ruffled and romantic; frivolous and pampered, a bit silly and naive. All of that's alive and underlined in the dress, with its explosion of lace and ruffles as well as its supernatural ability to repel the smallest speck of dirt. Scarlett is clean; free of messy thoughts, messy realities, and the kind of messy labor that could get a girl's best day dress for receiving courting gentlemen dirty or wrinkled. We will note briefly here the red hair bows and red belt, which stand out. They're not the point of this scene but they do underline Scarlett's boldness and serve as a bit of foreshadowing of the scandalous red dress to come.

The point; the Number One quality, the most clear and overwhelming aspect of Scarlett O'Hara in this introductory scene: She is a huge cupcake of whiteness sitting on a white platter situated in a white tableau.

Her dress is white, her flowers are white, her dog is white, her house is white, the blooms on the trees are white and even the peacocks on the lawn are white. In 1939, these aesthetic decisions were likely to have been made in service to the idea of purity (in a virginal if not racial sense), or to Scarlett's clean and pampered life; or to a general romanticism and naivete that defines her. They definitely tie Scarlett directly to Tara, foreshadowing all she will do to protect it because at some level, she is at one with the trappings of her life.

In 2020, it's almost impossible not to see it all in terms of her race. Scarlett isn't just spotless; she's spotless because of the enslaved Black people who work to keep her that way. She isn't just pampered; she's pampered by enslaved Black people in an apartheid system based on white supremacy. Her house and grounds aren't just beautifully groomed; they're done so by enslaved Black people, using resources and money generated off the backs of enslaved Black people.

Everything about Scarlett O'Hara's aesthetically pure, overwhelmingly white life is there because her father is a slave owner. Her whiteness becomes the entire point of this scene, looked at from that perspective. The explosion of white lace and ruffles becomes a metaphor for the aesthetic ideal of white supremacy.

The only people with sweat on their brow or dirt on their clothes are the enslaved. Everyone else is powdered and pretty, levitating above the dirt; untouched by it.

This depiction of white slave owners and plantation life is no more historically accurate than its depiction of faithful, happy slaves. You can't swan around a southern plantation in the springtime sun in 50 pounds of white lace and look like this. To depict her – and all the white people in this opening scene – so untouched by the world is a choice. Is it a choice in service to depicting their naivete or a choice to show them as romantic ideals of whiteness? Both, probably. Which is why it's so hard to dismiss this film as just a product of another time, even if it is hugely problematic.

The reason we still struggle with Gone with the Wind as an archetypal American motion picture is because the film tries to have it both ways, leaving decades and generations of audiences to debate its point of view. The overwhelming … fluffiness of this look; the sense of purity imbuing it, is intentional. The whiteness of the scene is intentional, even if it may not have been a direct reference to the racial realities it was depicting. The film is telling you in no uncertain terms that Scarlett is naive, privileged beyond measure, and unconcerned with the truth of her existence. At the same time, the film opts not to depict those realities or to depict them in the most romanticized of settings. Notice how the film neatly flips the symbolism of the opening scenes of the enslaved at work with this scene's closing shots of slave owners fretting over the future of their economic system:

The scene returns to the golden-hued nostalgia aesthetic of the opening credits, except instead of slaves shot against the dirt and at one with their tools of labor, it's white slave owners shot against the sky, rising up out of the land as if their ownership conveyed communion with it. It's a choice to depict them in such soaring, romantic imagery and it's not an easy choice to defend from today's perspective.

Even if directors Victor Fleming, George Cukor and Sam Wood ensured that the film occasionally tut-tutted the slave owners or took them to task for their perspective, it's hard not to read the entire opening scene as a celebration of an exploitive economic system based on the idea of white supremacy. And it's impossible not to see Scarlett's confection of a dress as a commentary – inadvertent or not – on the delusional quality that underlines white supremacy itself.

[Stills Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer via Tom and Lorenzo – Video Credit: via YouTube.com]

- Costumes

- Gone with the Wind

- One Iconic Look

- Vivien Leigh

Gone With the Wind Black and White Dress

Source: https://tomandlorenzo.com/2020/06/one-iconic-look-vivien-leigh-as-scarlett-ohara-in-gone-with-the-wind-movie-costume-analysis/

0 Response to "Gone With the Wind Black and White Dress"

Post a Comment