Differences in Late and Early Art Start in Hiv Patients

- Inquiry article

- Open up Access

- Published:

Early versus delayed initiation of antiretroviral therapy for Indian HIV-Infected individuals with tuberculosis on antituberculosis handling

BMC Infectious Diseases volume 12, Article number:168 (2012) Cite this commodity

Abstract

Groundwork

For antiretroviral therapy (Art) naive man immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected adults suffering from tuberculosis (TB), there is uncertainty about the optimal fourth dimension to initiate highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) subsequently starting antituberculosis treatment (ATT), in order to minimize mortality, HIV illness progression, and agin events.

Methods

In a randomized, open characterization trial at All Republic of india Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India, eligible HIV positive individuals with a diagnosis of TB were randomly assigned to receive HAART afterward two-4 or 8-12 weeks of starting ATT, and were followed for 12 months after HAART initiation. Participants received directly observed therapy short course (DOTS) for TB, and an antiretroviral regimen comprising stavudine or zidovudine, lamivudine, and efavirenz. Master end points were decease from whatsoever cause, and progression of HIV disease marked by failure of Art.

Findings

A total of 150 patients with HIV and TB were initiated on HAART: 88 received it after 2-4 weeks (early on Fine art) and 62 afterward eight-12 weeks (delayed ART) of starting ATT. There was no significant divergence in mortality between the groups later on the introduction of HAART. However, incidence of Fine art failure was 31% in delayed versus 16% in early ART arm (p = 0.045). Kaplan Meier illness progression complimentary survival at 12 months was 79% for early versus 64% for the delayed ART arm (p = 0.05). Rates of agin events were similar.

Interpretation

Early on initiation of HAART for patients with HIV and TB significantly decreases incidence of HIV disease progression and has skilful tolerability.

Trial registration

CTRI/2011/12/002260

Background

According to 2010 report of Joint United Nations Plan on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS), the global burden of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection was 33.3 million in 2009, with two.6 million incident cases and 1.8 one thousand thousand acquired allowed deficiency syndrome (AIDS) related deaths [1]. Tuberculosis (TB) in HIV-positive patients is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality, and therefore, a major constraint in the fight against HIV. Approximately 30% of HIV-infected persons all over the globe are estimated to accept latent TB infection [2]. Earth Health System (WHO) reported in 2010 that HIV-positive population experienced 11-thirteen% of 9.four meg incident TB cases worldwide, and 0.38 million TB related deaths during the previous year [iii]. TB is responsible for approximately one in four deaths in HIV patients globally [iv].

With near i fifth of the global burden, TB continues to be a public wellness claiming in India. Nearly forty% of Indian population is supposed to be infected with TB bacillus. The disease is responsible for 17.half-dozen% of deaths from catching diseases and for 3.v% of all causes of bloodshed [5]. Even though the endemic is maintained predominantly past non HIV TB cases, the situation gets complicated past Republic of india beingness the 3rd highest HIV burdened state. Every bit per 2009-2010 report from National AIDS Control Organization (NACO), the prevalence of HIV infection by the cease of 2008 was 0.29% in Indian adults [half dozen]. However, amidst TB patients in the country, HIV prevalence was equally loftier as six.7% in the same year co-ordinate to WHO estimates. Most 4.85% of incident TB cases in India were HIV positive in 2007 [five].

It is well established that HIV increases the risk for TB (acquisition, reactivation and reinfection), alters its clinical presentation, and reduces survival compared to patients with TB and no HIV infection [7–9]. With introduction of timely Fine art, the incidence of new TB infection can also be reduced past up to 90% [ten]. However, the question is when to start highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in a patient with HIV and TB (HIV-TB) who is taking handling for tuberculosis. On one mitt, early on initiation of HAART has the potential do good of reducing mortality and morbidity amidst recipients, on the other, physicians tend to defer it during TB treatment because of concerns that concomitant antituberculosis and antiretroviral handling may result in overlapping toxicities of drugs, low adherence to medications due to high pill burden, and college risk of paradoxical worsening of signs/symptoms of TB that is called allowed reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) [xi]. These factors impart considerable incertitude to the optimal timing of HAART initiation afterwards starting TB treatment.

There have been several studies that deal with the question of timing of HAART commencement in the setting of TB treatment in order to gain optimal event. Consummate results of some recently concluded randomized controlled trials that accost the issue are withal to come out [12, 13]. Some of the published studies have limitations like small sample size or lack of a control group, while a few others are primarily observational or retrospective in nature [12]. This paper presents the findings of a randomized controlled clinical trial that was conducted to compare early (ii-4 weeks) and delayed (viii-12 weeks) initiation of antiretroviral therapy after kickoff of antituberculosis treatment in Due north Indian HIV-infected adults with tuberculosis, in terms of outcomes like mortality and HIV disease progression.

Methods

Trial pattern

This randomized open-characterization trial was conducted at All Republic of india Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), a tertiary referral centre in New Delhi, India. Art-naïve individuals with HIV and recently diagnosed TB were enrolled and randomized into one of the two artillery of the study using one to one allocation ratio. One arm was scheduled to receive early on HAART, starting within two-4 weeks of commencement of antituberculosis treatment (ATT), and the other arm was to accept delayed HAART at 8-12 weeks afterwards starting ATT. For TB, patients were categorized co-ordinate to Indian Revised National Tuberculosis Command Programme (RNTCP) guidelines for thrice weekly straight observed treatment short-course (DOTS) [half dozen], and treated accordingly with free drugs provided by RNTCP. Antiretroviral drugs were provided costless of cost by NACO as part of the National AIDS Control Programme (NACP). Patients were followed for 12 months after HAART initiation. Ethics approval for the written report was obtained from the AIIMS institutional ethics commission.

Participants

All Fine art naïve HIV positive patients with active TB presenting in the hospital's Fine art Centre, DOTS Centre, infectious diseases and chest clinics, medical OPD, and wards were screened for eligibility. Subjects aged over xviii years, who had seven or fewer days of cumulative previous ART (unless taken during pregnancy to prevent mother-to-child-transmission), and who had not started ATT or received less than xiv days of the same, were eligible for entry into this study. Both confirmed and likely diagnoses of TB were permitted for inclusion. Confirmed cases included those with positive smear (using Ziehl Neelsen staining) for acid fast bacilli, and/or culture growth (on solid Lowenstein Jensen medium). Equally per WHO guidelines, likely diagnosis is based on the clinician's judgment where acid-fast bacilli are not demonstrable but sufficient clinical suspicion and/or radiological testify exists to initiate empiric TB therapy [14]. Liver function tests, i.e. SGOT, SGPT, and serum bilirubin, within 5 times the upper limit of normal range, and for female subjects, a negative urine pregnancy test were required for study entry. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, concomitant diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, severe disease (e.k. loss of consciousness, severe hempotysis etc.), and multi-drug resistant TB (MDR TB). MDR TB was excluded past a positive history of the same. Also, all sputum samples positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis were further screened using radiometric BACTEC 460 TB system.

Interventions

Patients who satisfied the screening criteria and provided written informed consent had their HIV status confirmed using Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) examination for HIV. Three sets of ELISA tests were washed according to NACO guidelines [xv, 16]. A sample testing reactive by the first test (SD BIOLINE HIV 1/2 ), underwent a second (PAREEKSHAK TRILINE HIV ½) and a third (PAREEKSHAK TRISPOT HIV i/2 ) exam based on different principles or different antigen systems. A sample testing reactive for all iii tests was termed HIV seropositive. Once HIV status was confirmed, patients were registered in the ART clinic with permanent ART numbers. All patients underwent pre-registration assessment, consisting of complete history and physical examination with measurement of height, weight and trunk mass index (BMI). Laboratory investigations for each included plasma HIV RNA viral load and CD4 cell count; complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation charge per unit (ESR), and serum biochemistry; smear for acid fast bacilli, culture and drug sensitivity for TB, and in some cases PCR of sputum or other specimens; diagnostic imaging like roentogram, ultrasonography, or computed tomography as indicated for TB diagnosis; histology or cytopathology of lymph nodes, abscesses or body fluids if indicated; routine urine and stool microscopy for evidence of other opportunistic infections; and testing for hepatitis B (HBsAg) and hepatitis C (anti-HCV IgG) infections.

As per the written report protocol, all HIV-TB patients received ART regardless of CD4 cell count. Antiretroviral regimen consisted of stavudine (d4T) 30 mg or zidovudine (ZDV) 300 mg twice daily, along with lamivudine (3TC) 150 mg twice daily and efavirenz (EFV) 600 mg one time daily. EFV was replaced with nevirapine at the finish of TB treatment. Patients who adult ZDV- induced anaemia during the form of HAART had ZDV replaced with d4T. All the report participants who had CD4 cell count <200/mm3, were given trimethoprim-sufamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ), one double strength tablet once daily for Pneumocystis prophylaxis.

Since baseline visit at the initiation of HAART, patients from both the groups were followed every calendar month till 12 months of Art. At follow up visits, each patient underwent a targeted history and physical examination, blood tests including serum biochemistry, CBC and ESR, and other relevant investigations based on clinical findings. CD4 jail cell counts were measured by menstruum cytometry using BD FACS CALIBUR and flourocein monoclonal antibodies (Beckton Dickenson Biosciences, California, USA) at baseline, ii, half dozen, nine, and 12 months of follow upwards. The HIV RNA viral load was measured by Roche Amplicor (Amplicor HIV-one Monitor Test, version 1.5, Branchburg, NJ: Roche Diagnostics; 2003) at baseline, six, and twelve months. A sputum test was washed before the outset of ATT, and at two and six months of ATT. Chest roentgenogram was washed at baseline, at six months mail ATT, and at the time of Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), if applicable. All patients coming for follow up visits were assessed for adverse events including IRIS, and the emergence of any opportunistic infections.

Outcomes

The principal end points of the study were decease from any crusade and antiretroviral handling failure, as a measure of progression of HIV illness. Death was documented from infirmary expiry certificates, or by communication with the patient's family or health intendance provider. As per NACO guidelines, a patient was said to have ART failure if whatsoever of the following occurred afterward at least six months of Fine art: - Clinical failure: new or recurrent WHO stage four condition; Immunological failure: a autumn of CD4 count to below pre-therapy baseline, or a fifty% turn down in CD4 count from the on – treatment peak value, or persistent CD4 levels below 100 cells /mm3; virological failure: plasma viral load >10,000 copies/ml [17]. The secondary finish points of the study were defined past safety and tolerability of ARV therapy, as assessed by the incidence of adverse events and proportion of subjects changing/ discontinuing ARV therapy because of the same. Outcome of TB treatment as divers by WHO [xviii], CD4 jail cell count and HIV RNA viral load, and assessment of general health by blood haemoglobin level and BMI at 6 and 12 months of ART were other secondary outcomes.

Sample size

The goose egg hypothesis of this report states that there is no deviation in terms of all cause mortality and progression of HIV disease betwixt HIV patients with tuberculosis who start HAART early (at 2-iv weeks) and those who receive it delayed (at 8-12 weeks) after start of antituberculosis chemotherapy. Since it was one of the commencement studies on this topic from India, a target sample size of 75 patients per arm was decided as the sample size of convenience as per protocol.

Randomization

2 weeks later on starting ATT, patients were allocated by computer generated sequence of random numbers to one of the 2 groups of the study in ane to one ratio, following simple randomization. The sequence was generated past the statistician, and the written report being open label, was known to the inquiry team, which enrolled the participants besides as assigned them to study groups. Fine art physicians were informed of each patient'due south allocation after randomization. Neither participants nor intendance providers were blinded to interventions.

Statistical methods

All the pertinent clinical and laboratory data on individual subjects were entered into the case written report forms, and transferred to an electronic data base with 100% retrospective data auditing. The electronic data was exported into the STATA software, version 11, for statistical analysis. All the analyses were performed as per the modified intention-to-treat principle with inclusion of only those patients who initiated HAART at the place of the study. The analyst was kept blind to the interventions. Primary finish points of the study were assessed using Kaplan Meier assay and log rank comparisons. Fisher's exact examination was used for analysis of categorical variables, and Student's t-exam for continuous variables.

Results

Participants

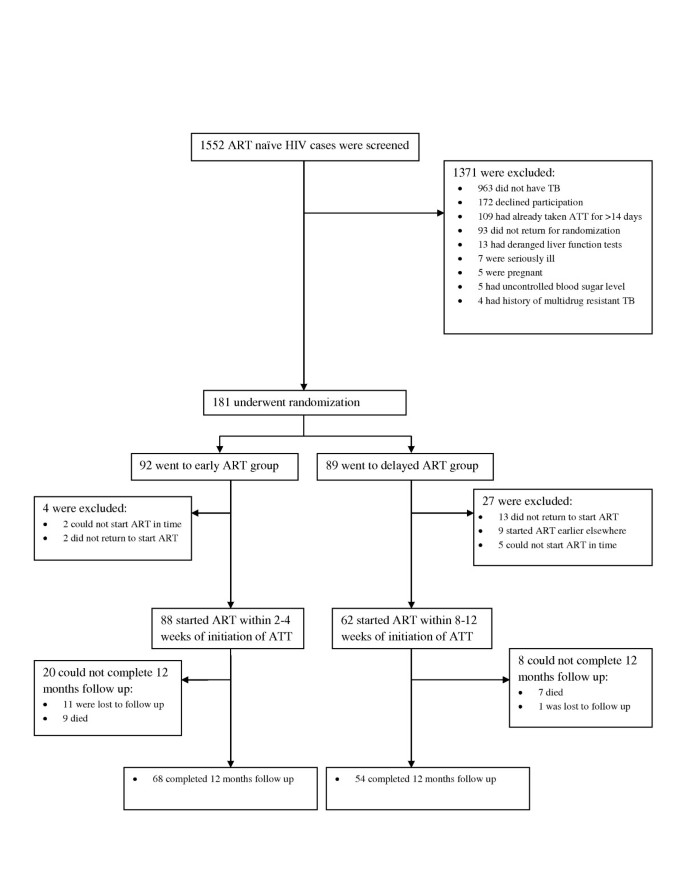

Figure 1 shows the screening and enrolment of participants in the report. A full of 181 patients were randomized, with 92 going to the early Art arm and 89 to the delayed ART arm. 15 of them (2 from early ART and 13 from delayed ART groups) did not come dorsum for HAART initiation, while 7 others (two from early Fine art and five from delayed ART artillery) could not outset HAART before completion of their ATT. Besides, nine patients from the delayed ART arm started HAART earlier elsewhere and did not come for follow upward. The remaining 150 patients were initiated on HAART as role of the report: 88 received it within 2-iv weeks (early group) of starting ATT, and 62 within 8-12 weeks (delayed group) of the aforementioned. At the time of the final analysis, 122 (81.3%) patients out of 150 had completed follow up of 12 months, 68 in early and 54 in delayed Art groups respectively. Sixteen (10.7%) patients, 9 (x.2%) from early and 7 (11.3%) from delayed Art group, had died, and 12 (8.0%) were lost to follow up, 11 (12.5%) in the early on arm and ane (1.6%) in the delayed arm. 'Lost to follow up' was defined past failure to visit the hospital for three consecutive months. Out of the full 12 patients lost to follow up, 5 were untraceable (no telephonic contact could be fabricated), iv were transferred to other Art centres due to spatial relocation, and 3 had defaulted treatment.

Screening, Enrolment, and Follow-up of written report participants.

Recruitment

All the patients enrolled till March 31, 2011, were included in the final analysis. The duration of follow upwardly in the study was calculated every bit the time from initiation of HAART to decease, loss to follow upwardly, or the completion of 12 months whichever came earlier.

Baseline data

Grouping-wise baseline demographic and clinical characteristic of 150 enrolled patients is presented in Table 1. Both the groups were found to be homogeneous with each other, having similar initial BMI, age distribution, and sex ratio (with significant male predominance). The median gaps between beginning of ATT and Art in early and delayed groups were nineteen and 63 days respectively. No significant difference was seen between the groups in terms of baseline median CD4 count, viral load, and other laboratory parameters. Most patients were new cases of TB, and therefore, received DOTS category I ATT (94.three% in the early on ART group, 98.4% in delayed Fine art group). According to RNTCP guidelines, they received isoniazid (H) 600 mg, rifampicin (R) 450 mg (600 mg if body weight ≥sixty kg), pyrazinamide (Z) 1500 mg, and ethambutol (E) 1200 mg thrice weekly during the intensive handling phase of ii months, followed past isoniazid 300 mg and rifampicin 450 mg thrice weekly in the continuation phase for iv months (2H3R3ZthreeE3 + 4H3R3). Six patients, who had been treated for a dissimilar episode of TB in the by, received DOTS category 2 ATT (v in early Art and one in delayed Fine art grouping). Intensive stage of RNTCP DOTS category Ii ATT lasts for three months, with streptomycin (Southward) 750 mg (500 mg if age >50 years) given thrice weekly for first two months, in addition to H3RiiiZthreeEiii. In continuation phase, category Ii patients received isoniazid, rifampicin, and ethambutol for 5 months (2HiiiRthreeZ3E3South3 + 1HiiiR3ZthreeE3 + 5HiiiRiiiEast3) [5, half-dozen]. Even though the early ART group has patently higher number of cases of EPTB with dissemination, no statistically meaning difference was institute between the two arms of the report with respect to any type of TB individually, or overall.

Primary outcome

All 150 patients, 88 in the early Art group and 62 in the delayed Fine art group, were included in the assay for primary result measures of death from any cause and Fine art failure. The overall mortality was found to be 10.vii% (16/150), 10.2% (9/88) in the early ART group and 11.3% (7/62) in the delayed Fine art group (p value = 0.773). This translates to death rates of 13.8 and 13.0 per 100 person years for the two groups respectively. It was seen that out of 16 patients who died during the follow up, xi (68.8%) had baseline CD4 value <100 cells/mm3, seven coming from the early on and four from the delayed Art groups.

Table 2 shows the comparative outcome of antiretroviral treatment in the two groups of the study. The incidence of immunological failure was seen to be significantly higher at 22.six% (14/62) in the delayed ART grouping, in comparing with ix.1% (viii/88) in the early Fine art grouping (p = 0.033). Only one patient of all 150 went into clinical failure, and he was from the delayed ART group (0.0% vs.1.6%, p = 0.413). Virological failure was documented in 8 patients from each group, its incidence existence 9.ane% in the early and 12.9% in the delayed ART groups (p = 0.592). Rate of overall treatment failure was observed to be almost double in the delayed ART group (31%), as compared to that in the early ART group (sixteen%) (p = 0.045). The incidence of failure of ARV therapy in the entire study population was 22%.

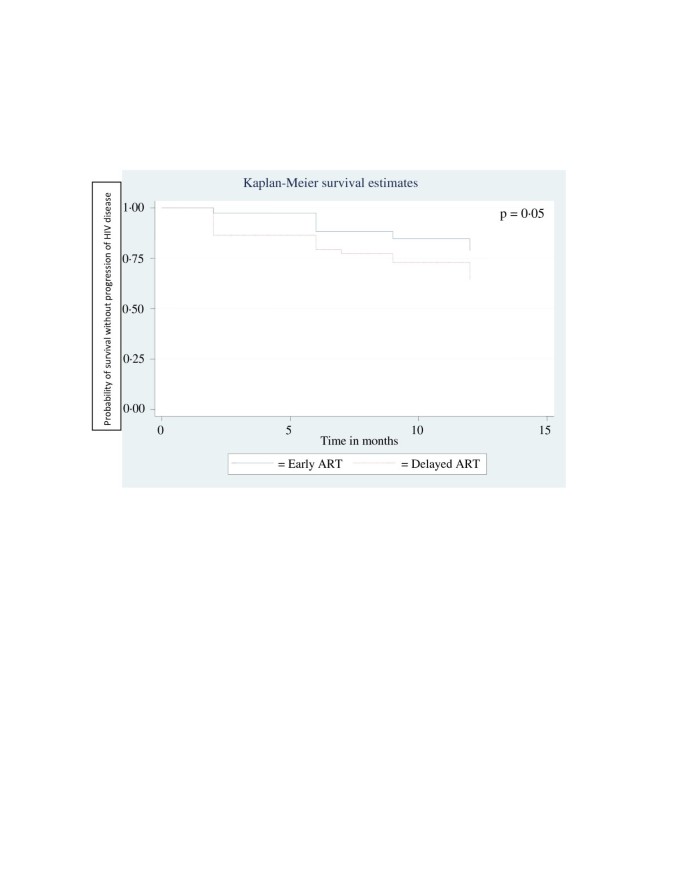

Based on the incidence of various types of treatment failure over the follow up menses, 12 months HIV affliction progression gratuitous survival rate was calculated for each group. At 79%, it was significantly better for the early ART group, as confronting 64% for the delayed Fine art group (p = 0.05). A Kaplan-Meier disease progression complimentary survival curve was plotted on the basis of the same calculation and is depicted in Effigy 2.

Kaplan Meier Curve of Survival without progression of HIV disease for 12 Months with Early and Delayed ART.

Secondary outcomes

Among the adverse events, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome was diagnosed in ix patients (10.2%) in the early ART group and six patients (9.vii%) in the delayed ART group (p = 0.571). The median time of occurrence of IRIS after initiation of HAART was 73 and 68.5 days in the early on and delayed ART groups respectively. All cases of IRIS were of mild to moderate severity, and none of them required any interruption of HAART or management with steroids. The affected patients responded well to antipyretic (paracetamol) and analgesics (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs).

The incidence of other adverse events was also non significantly different betwixt the groups (23.9% in the early and 22.half-dozen% in the delayed ART grouping, p = 0.855). 7 patients (four%) required a change in the antiretroviral regimen, in which zidovudine was switched for stavudine, due to the development of drug induced astringent anaemia. Four (4.five%) of them came from the early on ART group and iii (iv.8%) from the delayed ART group (p = 0.612). No change in therapy was needed for any other adverse event. All of them were managed appropriately by experts at the respective follow upward clinics of the patients. No death in the study population was attributed to any of the adverse events.

Effect of antituberculosis handling was categorised as per the WHO definitions [nineteen]. At the time of final analysis, all study participants had completed their prescribed ATT courses. Half dozen (6.viii%) patients from early and four (6.4%) from delayed ART group had died, and farther 6 patients from the early ART group were lost to follow upwardly before the completion of their antituberculosis therapy. No significant difference was seen in the outcome of TB treatment at the completion of ATT betwixt the groups (p = 0.105), equally summarized in Table 2. During follow up, one case of relapse of TB has been reported from each grouping till date.

Response of the patients to overall handling was like in each grouping in terms of full general wellness parameters like haemoglobin level, liver part tests and body mass index (Table iii).

Discussion

This is the first written report sponsored by National AIDS Control Organisation, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of Republic of india in this topic. The results of this written report bear witness that once highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is started, there is no significant departure in mortality between HIV-TB patients who were started on HAART ii-4 weeks after initiation of antituberculosis treatment (early on ART grouping), and those who received information technology viii-12 weeks after starting ATT (delayed ART group). All the same, the adventure for progression of HIV disease, as estimated past onset of failure of ARV therapy, increases significantly if initiation of HAART is deferred from 2-four weeks to 8-12 weeks (xvi% vs. 31% hazard, p = 0.045). The incidence of IRIS and other agin events, and issue of TB treatment are similar between the groups.

To decide the optimal timing for initiation of HAART after starting ATT in HIV-TB patients has been listed as a priority research question for resources express settings past WHO [20]. Several studies have been involved with the job of finding a definitive answer to information technology then that mortality and serious morbidity could be minimized in this patient population [12, 21]. A contempo trial by Abdool Karim et al shows that starting antiretroviral therapy at CD4 prison cell count <500/mm3 during handling for AFB smear-positive TB (integrated therapy) reduces mortality by 56% in HIV-TB cases, as compared to delaying it until the completion of TB therapy (sequential therapy) [22]. They take reported an all-cause mortality rate of 5.4 per 100 person-years in the integrated therapy arm every bit compared to 12.1/100 per twelvemonth in the sequential therapy arm (p = 0.003). Their integrated therapy arm corresponds roughly with both the groups of the present study taken together, where the combined bloodshed rate was observed to be 13.4/100 per twelvemonth. The principal reason for this apparently higher mortality observed here may be that the current study had a much college percent (77.3%) of patients in WHO stage four HIV illness at baseline than that (4.9%) in the South African written report.

Another trial at Cambodia has shown in its preliminary written report that in that location is a pregnant survival advantage of 34% in starting HAART at two weeks (early arm) rather than at 8 weeks (late arm) afterward initiation of TB treatment [xix, 23]. They observed a mortality of 17.viii% in the early arm against 27.four% in the late arm (p = 0.002). On comparison, it tin can exist seen that the Cambodian study reports a much higher mortality rate in both the groups than the nowadays study despite both following a similar protocol in terms of timing of Art initiation. One of the important reasons for this divergence may be their sectional enrolment of patients with CD4 count <200/mmiii. For the aforementioned reason, it tin can be argued that results of the current study are more than generalizable than the Cambodian one. Moreover, while the present research work has excluded the deaths that might have occurred betwixt the starting of ATT and Fine art in both the groups, this fraction was taken into account while calculating mortality in the Cambodian projection.

The current research was designed to assess and compare the response of HAART in HIV-TB patients who started information technology 2-4 weeks afterward starting TB therapy and those who received it 8-12 weeks after starting TB treatment. CD4 prison cell counts and plasma viral load have been considered important markers for assessment of response to ARV therapy and disease progression [24–26]. Previous studies accept shown that co-infection with TB results in reduced survival, increased risk for other opportunistic infections and elevations in HIV replication [27, 28]. Increased HIV replication is attributed to activation of latently infected cells, and promotion of infection in uninfected lymphocytes and macrophages. HIV genetic diverseness is also increased in the presence of active TB infection [29–31]. The results of this report indicate that these processes may exist meaning enough to cause failure of ARV therapy after a few months, warranting a switch to second line Fine art. Some previous studies take demonstrated that death in HIV-TB patients inside the first few months of TB handling may be related to TB, whereas late deaths are owing to HIV affliction progression [32–34]. Therefore, information technology can be extrapolated that in due course of time a differential disease progression might fifty-fifty interpret into a significant difference in mortality between the two groups of the study. In light of this observation, the nowadays piece of work supports 2010 WHO recommendations for the management of HIV-TB cases: [35]

- 1.

Offset Fine art in all HIV-infected individuals with agile TB, irrespective of the CD4 cell count.

- 2.

Outset TB treatment outset, followed past ART as soon as possible after (and inside the first eight weeks).

The overall incidence of Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome observed hither (10.0%) is close to that reported for the integrated therapy arm (12.4%) by Abdool Karim et al[27]. The Cambodian trial has reported a significantly college incidence of IRIS in the early ART arm (iv.03 per 100 patient months) than in the late arm (one.44/100 pm, p <0.0001) [28], but no such difference could be seen in the present study.

This research work has a few limitations. Here all cause mortality was taken as the principal consequence instead of disease-specific expiry rate. While the latter would exist more suitable for assessment of response to Art, in that location were logistic difficulties in ascertaining the exact cause of most of the deaths, equally they happened away from the hospital. Another limitation is introduced past the uneven number of lost to follow upwards patients (eleven in early on Art and one in delayed Fine art) in the two groups of the written report, which could affect its results. But 7 of them from early Fine art arm were known to be alive by the end of 12 months since they were initiated on ART, and the consideration of the worst outcome for the five (four in early ART arm and one in delayed ART arm) untraceable patients did not alter the overall results of the study significantly. In addition, as decided in the canonical protocol, sample size of the study was based on a target of convenience rather than on power calculations. In this study given a baseline charge per unit of 10% bloodshed, in that location was an 80% power to observe a deviation of xviii% mortality between early and delayed ART groups. However, despite these limitations, being ane of the offset studies on this topic from India, the present work will serve as one of the resource for early starting of ARV treatment under National AIDS Control Programme. It volition also help for whatsoever time to come metaanalysis for the timing of HAART initiation in HIV-TB cases.

This written report presents important research findings regarding optimal time to initiate Art in HIV-TB cases so that detrimental effects of both the diseases can be minimized. Since it included HIV patients irrespective of baseline CD4 jail cell counts and with unlike types of TB, its results can be fairly generalized. It brought to low-cal the observation that starting early ART in HIV-TB patients helps control the progression of HIV affliction later on, and hence, it suggests that all such patients must be started on HAART equally soon as possible later on initiation of TB treatment.

References

-

The United nations Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS): 2010 report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic. 2010, UNAIDS. Technical Report number: UNAIDS/10.11E, Geneva

-

Earth Health Organization (WHO): HIV/AIDS: Tuberculosis and HIV [Net]. 2011, Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/topics/tb/en/index.html (accessed April xiii)

-

WHO: Global Tuberculosis Command. WHO study. 2010

-

UNAIDS: HIV Data: Epidemiology. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/Epidemiology/latestEpiData.asp (accessed April 8, 2011)

-

Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP): TB India 2010: RNTCP Condition Report. 2010, Ministry of Wellness and Family Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi

-

National AIDS Control Organization (NACO): 2009-2010: Almanac Condition report. 2010, Department of AIDS Control, Ministry of Health and Family unit Welfare, Govt. of Bharat, New Delhi

-

Charles LD, Peter MS, Gisela FS, et al: An outbreak of tuberculosis with accelerated progression amongst persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: an analysis using restriction-fragment–length polymorphisms. N Engl J Med. 1992, 326 (4): 231-235. x.1056/NEJM199201233260404.

-

De Erect KM, Soro B, Coulibaly IM, et al: Tuberculosis and HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa. JAMA. 1992, 268: 1581-1587. x.1001/jama.1992.03490120095035.

-

Wilkinson D, Moore DAJ: HIV-related tuberculosis in South Africa–clinical features and outcome. S Afr Med J. 1996, 86 (1): 64-67.

-

Badri 1000, Wilson D, Wood R: Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on incidence of tuberculosis in South Africa: a cohort written report. Lancet. 2002, 359 (9323): 2059-2064. x.1016/S0140-6736(02)08904-3.

-

Sanguanwongse North, Cain KP, Suriya P, et al: Antiretroviral therapy for HIV –infected Tuberculosis patients saves lives merely needs to be used more than oftentimes in Thailand. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008, 48 (2): 181-189. x.1097/QAI.0b013e318177594e.

-

Piggott DA, Karakousis PC: Timing of antiretroviral therapy for HIV in the setting of TB treatment. Clin Dev Immunol [Net]. 2010, 2011: 103917-10.1155/2011/103917. Available at: http://world wide web.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3017895/(accessed April 5, 2011) DOI:

-

ACTG A5221. Firsthand Versus Deferred Start of Anti-HIV Therapy in HIV Infected Adults Being Treated for Tuberculosis. 2011, Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/evidence/NCT00108862 (accessed March 31)

-

World Health System: Handling of Tuberculosis: Guidelines. 2010, WHO, 4

-

NACO: HIV Testing policy and functioning of VCTC. 2001, New Delhi, Ministry of Health and Family welfare, Govt. of India

-

NACO: National AIDS Prevention and Control Policy. 2002, New Delhi, Ministry building of Health and Family Welfare, Govt. of India

-

NACO: Antiretroviral Therapy guidelines for HIV infected adults and adolescents including post exposure prophylaxis. 2007, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Govt. of Bharat, New Delhi

-

WHO: Tuberculosis: Definitions of Tuberculosis cases and treatment outcomes. 2011, Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2007/table5/en/index1.html (accessed March 31)

-

National Found of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID): NIH-funded study finds early HAART during TB handling boosts survival rate in people co-infected with HIV and TB. 2010, NIH News

-

WHO: TB/HIV Working Group. Priority research questions for TB/HIV in HIV-prevalent and resource-express settings. 2010, Earth Health Organization

-

Blanc FX, Havlir DV, Onyebujoh PC, et al: Handling strategies for HIV-infected patients with tuberculosis: ongoing and planned clinical trials. J Infect Dis. 2007, 196 (suppl 1): S46-S51.

-

Abdool Karim SS, Naidoo Grand, Grobler A, et al: Timing of initiation of antiretroviral drugs during Tuberculosis therapy. Due north Engl J Med. 2010, 362 (8): 697-706. 10.1056/NEJMoa0905848.

-

Blanc FX, Sok T, Laureillard D, et al: Significant enhancement in Survival with early (ii weeks) vs. late (eight weeks) initiation of highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) in severely immunosuppressed HIV-infected adults with newly diagnosed tuberculosis. 2010, Presented at: Proceedings of the XVIII International AIDS Society Conference, Vienna, 18-23. Austria. (Abstract THLBB106)

-

Zargoza-Marcias Eastward, Cosco D, Nguyen ML, et al: Predictors of success with highly active antiretroviral therapy in an antiretroviral-naive urban population. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010, 26 (2): 133-138. 10.1089/aid.2009.0001.

-

Hogg RS, Yip B, Chan KJ, et al: Rates of illness progression by baseline CD4 cell count and viral load after initiationg triple –drug therapy. JAMA. 2001, 286 (twenty): 2568-2577. 10.1001/jama.286.20.2568.

-

Jaen A, Esteve A, Miro JM, et al: Determinants of HIV progression and assessment of the optimal time to initiate highly agile antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008, 47 (two): 212-220. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815ee282.

-

Whalen C, Okwera A, Johnson J, et al: Predictors of survival in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. The Makerere University-Case Western Reserve University Research Collaboration. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996, 153: 1977-1981.

-

Whalen CC, Nsubuga P, Okwera A, et al: Impact of pulmonary tuberculosis on survival of HIV-infected adults: a prospective epidemiologic study in Uganda. AIDS. 2000, 14 (9): 1219-1228. ten.1097/00002030-200006160-00020.

-

Toossi Z: Virological and immunological affect of tuberculosis on homo immunodeficiency virus type 1 disease. J Infect Dis. 2003, 188 (8): 1146-1155. x.1086/378676.

-

Morris Fifty, Martin DJ, Bredell H, et al: Human Immunodeficiency Virus1 RNA Levels and CD4 Lymphocyte Counts, during Treatment for Agile Tuberculosis, in S African Patients. J Infect Dis. 2003, 187 (12): 1967-1971. 10.1086/375346.

-

Nakata One thousand, Rom WN, Honda Y, et al: Mycobacterium tuberculosis enhances human immunodeficiency virus-one replication in the lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997, 155 (three): 996-1003.

-

Manosuthi W, Chottanapand South, Thongyen S, et al: Survival rate and risk factors of mortality among HIV/tuberculosis-coinfected patients with and without antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006, 43 (i): 42-46. 10.1097/01.qai.0000230521.86964.86.

-

Nunn P, Brindle R, Carpenter L, et al: Cohort study of human being immunodeficiency virus infection in patients with tuberculosis in Nairobi, Kenya. Analysis of early (6-calendar month) mortality. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992, 146 (4): 849-854.

-

Churchyard GJ, Kleinschmidt I, Corbett EL, et al: Factors associated with an increased case-fatality rate in HIV-infected and not-infected South African gold miners with pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000, 4: 705-712.

-

World Health Organisation: Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents. 2010, WHO

Pre-publication history

-

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://world wide web.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/12/168/prepub

Acknowledgement

Nosotros thank National AIDS Control Arrangement (NACO), Ministry of Wellness & Family Welfare, Government of India for funding support to this written report. We also give thanks and acknowledge the support of AIIMS ART dispensary staff during the enrolment of patients.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Additional information

Competing interest

We declare that we take no conflicts of involvement.

Authors' contributions

SS provided inputs to the study design, helped in information analysis and interpretation, wrote the manuscript, and did final editing. SRC, SG, EM and SN reviewed literature, and helped in interpreting data and writing the manuscript. AH and KN collected data, and conducted laboratory tests for CD4 cell count and plasma viral load. RS helped in data collection. SV did data analysis. SSK, SJC, and MRT edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the last manuscript.

Funding

National AIDS Control Organization (NACO), Ministry building of Health & Family unit Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi, India.

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Artistic Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted employ, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original piece of work is properly cited.

Reprints and Permissions

Nigh this article

Cite this article

Sinha, S., Shekhar, R.C., Singh, One thousand. et al. Early on versus delayed initiation of antiretroviral therapy for Indian HIV-Infected individuals with tuberculosis on antituberculosis treatment. BMC Infect Dis 12, 168 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-12-168

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/1471-2334-12-168

Keywords

- Antiretroviral

- Early on

- Delayed

- HIV

- Tuberculosis

Source: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2334-12-168

0 Response to "Differences in Late and Early Art Start in Hiv Patients"

Post a Comment